FCC’s proposed rule changes on net neutrality violate a host of international obligations

Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

— Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

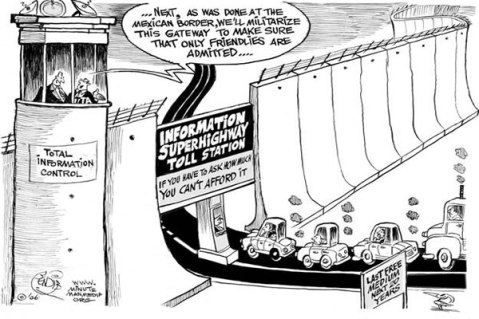

With one month to go before the public comment period ends on the Federal Communications Commission’s recent vote to advance a proposal that would end net neutrality and create a system of paid-prioritization online, a new report has come out criticizing the FCC’s actions as potentially undermining the U.S. government’s international obligations regarding freedom of expression.

The legal analysis issued Monday by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe – an inter-governmental organization that counts the United States as one of its 57 members – found that the rules on net neutrality (the principle that internet service providers treat all data equally and not discriminate based on content or price paid) proposed by the FCC may violate one or more of the following international accords to which the United States has subscribed: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights, and the 1990 OSCE Copenhagen Document.

Prepared for the Office of the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media by George Washington University Law School Professor Dawn Carla Nunziato, the report points out that Article 19 of both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the ICCPR protects the right to freedom of expression and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Despite this international obligation of the U.S. government, the FCC has proposed rules that would replace the so-called Nondiscrimination Rule with a No Commercially Unreasonable Practices Rule. As Prof. Nunziato explains it, “Permitting ‘commercially reasonable’ practices by broadband providers will allow – and indeed encourage – broadband providers to experiment with business models that include paid prioritization – and even exclusive paid prioritization – upon individualized negotiations with edge providers (providers of content, applications, and services).”

In practice, what this would mean is that broadband providers would be able to negotiate exclusive pay-for-priority arrangements with individual content providers, permitting broadband providers to anoint exclusive premium content providers “and effectively become censors of other disfavored, poorly funded, or unpopular content, by choosing not to favor such content for transmission to subscribers.”

For example, an internet service provider like Comcast “could enter into a deal with Foxnews.com to anoint it as the exclusive premium news provider for all Comcast subscribers, while comparatively disadvantaging all other news providers.”

Similarly, the FCC’s Proposed Rules would allow a broadband provider like Verizon to enter into an arrangement with the Republican National Committee to anoint it as the exclusive premium political site for all Verizon subscribers, while disadvantaging the Democratic National Committee’s and other political sites.

She goes on to describe other possible effects of this rule change:

Otherwise protected speech – a blog critical of Verizon’s latest broadband policies, a disfavored political party’s website – could be disfavored by broadband providers and not provided to Internet users in a manner equal to other, favored Internet content – subject only to the Proposed Rules’ vague prohibition against commercially unreasonable conduct. Such a regime would endanger the free flow of information on the Internet, would threaten freedom of expression and freedom of the media, and would herald the beginning of the end of the Internet as we know it.

The possibility of being sidelined by the ISPs could lead to “further entrenched market power by dominant content and applications providers, self-censorship by content providers who might alter their content to make it more palatable to broadband providers, and a reduction in the overall amount of speech that is meaningfully communicated as a result of content not being delivered effectively to its intended audience.”

These very real prospects led the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, Dunja Mijatovic, to weigh in on the controversy yesterday.

“The proposed rules will allow telecommunications providers to discriminate against content which may conflict with their political, economic or other interests,” Mijatovic said in a letter to FCC Chair Tom Wheeler. “This would contradict international standards, OSCE commitments on free expression and freedom of the media and longstanding U.S. First Amendment principles.”

Besides U.S. international commitments on freedom of information, the net neutrality controversy spurred by the FCC and its chairman Tom Wheeler raises questions of U.S. compliance with its anti-corruption obligations under the UN Convention against Corruption. As a state party to this Convention, the United States has agreed to taking measures to prevent conflicts of interest and corruption in both the public and private sphere. In particular,

Each State Party shall, in accordance with the fundamental principles of its domestic law, endeavour to adopt, maintain and strengthen systems that promote transparency and prevent conflicts of interest.

Each State Party shall endeavour, where appropriate and in accordance with the fundamental principles of its domestic law, to establish measures and systems requiring public officials to make declarations to appropriate authorities regarding, inter alia, their outside activities, employment, investments, assets and substantial gifts or benefits from which a conflict of interest may result with respect to their functions as public officials. …

Preventing conflicts of interest by imposing restrictions, as appropriate and for a reasonable period of time, on the professional activities of former public officials or on the employment of public officials by the private sector after their resignation or retirement, where such activities or employment relate directly to the functions held or supervised by those public officials during their tenure.

Yet, the powerful chairmanship of Wheeler at the FCC demonstrates once again how the United States routinely flouts this obligation to prevent conflicts of interests. Prior to joining the FCC, Wheeler worked as a venture capitalist and lobbyist for the cable and wireless industry, with positions including President of the National Cable Television Association (NCTA) and CEO of the Cellular Telecommunications & Internet Association (CTIA). He also raised over $500,000 for Barack Obama’s two campaigns.

As a reward for this financial backing, President Obama then appointed him to his current position where is empowered with rewriting the rules for the industry that once employed him. This sort of patronage is not only prohibited under the Convention against Corruption, but now, as we see, is leading to multiple violations of international principles, as documented by the OSCE in its report issued Monday.

“The Internet was conceived as an open medium with the free flow of information as one of its fundamental characteristics,” Mijatovic said upon the report’s release. “This should be guaranteed without discrimination and regardless of the content, destination, author, device used or origin.”

Mijatovic expressed her hope that her recommendations will be taken into consideration by the FCC.

The legal analysis of the proposed net neutrality rule changes is available here. To comment to the FCC regarding its proposed rules regarding net neutrality, click here.

A very accessible, succinct explanation of the FCC’s proposed rule changes was offered recently by John Oliver on his cable show Last Week Tonight:

With U.S. in uncorrected violation of CWC, Supreme Court rules on ‘unimaginable’ case

The Supreme Court ruled today that a 1998 federal law intended to enforce the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention cannot be used to prosecute individuals where state laws would be sufficient. The justices unanimously threw out the conviction of Carol Anne Bond of Lansdale, Pa., who had been prosecuted under the CWC law for using toxic chemicals that caused a thumb burn on a friend with whom her husband had an affair.

The case raises several disturbing questions about how the United States views its obligations under international law. For one, as legal analyst Lyle Denniston pointed out, although the justices did not strike down the law as beyond Congress’s constitutional powers, the decision in Bond v. United States “left in lingering doubt just how far Congress may go to pass a law to implement a world treaty.”

Perhaps more troubling though is the fact that this case even exists and was heard by the Supreme Court in the first place. It could be said that its very existence makes a mockery of international law.

When the case was argued before the court last November, Justice Anthony Kennedy told the government’s lawyers that it is “unimaginable that you would bring this prosecution.” The Justices seemed to agree that the case was a “curious” one: a federal criminal prosecution, with a potential life sentence, of a woman who sought revenge by spreading poisonous chemicals on a door knob, a car door handle, and a mailbox in the hopes that her husband’s mistress would touch the chemicals and suffer unspecified health consequences.

Bond had likely violated a number of laws in her state of Pennsylvania, but was only charged under state law for making harassing telephone calls and letters, and state officials declined to prosecute her with assault. She had pleaded guilty to the federal crime of using a “chemical weapon,” on condition that she could later challenge the prosecution.

Although she was convicted under the 1998 law, Monday’s decision struck down that conviction because the law did not even apply to what she did, according to the Court’s majority.

In this case, it seems fairly clear that the justices were correct that prosecutors had overreached when they charged Bond under a federal statute which was expressly intended to ensure U.S. compliance with its international obligations as a state party to the CWC, not to prosecute individuals for using makeshift chemical agents in a clumsy attempt to exact revenge for adultery.

As one scholar described the treaty, it is “the most complex disarmament and nonproliferation treaty in history,” designed specifically to ensure that state parties relinquish weapons that the CWC expressly prohibits. Katharine York elaborated on the purpose of the CWC in article in the Denver Journal of International Law and Policy last month:

As a starting point, Article I identifies the general obligations of State Parties under the CWC:

1. Each State Party to this Convention undertakes never under any circumstances:

(a) To develop, produce, otherwise acquire, stockpile or retain chemical weapons, or transfer, directly or indirectly, chemical weapons to anyone;

(b) To use chemical weapons;

(c) To engage in any military preparations to use chemical weapons;

(d) To assist, encourage or induce, in any way, anyone to engage in any activity prohibited to a State Party under this Convention.

2. Each State Party undertakes to destroy chemical weapons it owns or possesses, or that are located in any place under its jurisdiction or control, in accordance with the provisions of this Convention.

3. Each State Party undertakes to destroy all chemical weapons it abandoned on the territory of another State Party, in accordance with the provisions of this Convention.

4. Each State Party undertakes to destroy any chemical weapons production facilities it owns or possesses, or that are located in any place under its jurisdiction or control, in accordance with the provisions of this Convention.

5. Each State Party undertakes not to use riot control agents as a method of warfare.

The United States government, as a state party to the convention, is in clear violation of a number of these provisions. For starters, it has used chemical weapons expressly prohibited under the treaty, as well as others with an ambiguous status. As WikiLeaks revealed in 2007, the U.S. deployed at least 2,386 “non-lethal” chemical weapons during the invasion and occupation of Iraq.

Appearing in a 2,000-page battle planning leak, the items are labeled under the military’s own NATO supply classification as “chemical weapons and equipment.”

As WikiLeaks explained,

In the weeks prior to the March 19, 2003 commencement of the Iraq war, the United States received a widely reported rebuke from its primary coalition partner, the United Kingdom, over statements by the then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld suggesting that the US would use CS gas for “flush out” operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Subsequently Washington has been quiet about whether it has deployed CS gas and other chemical weapons or not.

The use of chemical weapons such as CS gas for military operations is illegal. The Chemical Weapons Convention of 1997, drafted by the United Kingdom and ratified by the United States, declares “Each State Party undertakes not to use riot control agents as a method of warfare”. Permissible uses are restricted to “law enforcement including domestic riot control.”

The U.S. use of depleted uranium in Iraq is another cause for concern. In Fallujah – which was targeted mercilessly by U.S. forces in 2004 – the use of depleted uranium has led to birth defects in infants 14 times higher than in the Japanese cities targeted by U.S. atomic bombs at close of World War II, Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

A 2002 UN working paper on depleted uranium argued that its use may breach the Chemical Weapons Convention, as well as several other treaties. Yeung Sik Yuen writes in Paragraph 133 under the title “Legal compliance of weapons containing DU as a new weapon”:

Annex II to the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material 1980 (which became operative on 8 February 1997) classifies DU as a category II nuclear material. Storage and transport rules are set down for that category which indicates that DU is considered sufficiently “hot” and dangerous to warrant these protections. But since weapons containing DU are relatively new weapons no treaty exists yet to regulate, limit or prohibit its use. The legality or illegality of DU weapons must therefore be tested by recourse to the general rules governing the use of weapons under humanitarian and human rights law which have already been analysed in Part I of this paper, and more particularly at paragraph 35 which states that parties to Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 have an obligation to ascertain that new weapons do not violate the laws and customs of war or any other international law.

Further, the United States is in flagrant violation of its obligations to destroy its chemical weapons stockpiles. When the CWC went into effect 17 years ago, the U.S. declared a huge domestic chemical arsenal of 27,771 metric tons to the OPCW. Although it has destroyed about 90% of its chemical weapons, the U.S. still maintains a stockpile of 2,700 tons according to the Centers for Disease Control, missing two deadlines to destroy the weapons.

But curiously, it is not this issue that is commanding headlines, but rather the misuse of the 1998 federal statute in a way that it was never intended. The case of Bond’s prosecution and today’s Supreme Court ruling holds a number of lessons, one of which being the government’s implied view of the applicability of law – namely that laws are to be used only in prosecuting rogue individuals, but not in reining in the rogue U.S. government.

As the Supreme Court ruled in Bond v. the United States, “The Government would have us brush aside the ordinary meaning [of chemical weapon] and adopt a reading … that would sweep in everything from the detergent under the kitchen sink to the stain remover in the laundry room. Yet no one would ordinarily describe those substances as ‘chemical weapons.’”

Yet, even while stretching this law beyond its logical applicability, actual violations of the CWC are swept under the rug as if they don’t even occur. This is a clear indication of the government’s view that it is indeed above the law, that the force of law is only to be used against the powerless, and certainly not against those in power.