Congress authorizes perpetual lawlessness in the ‘war on terror’

In two major votes this week, the U.S. Congress gave a green light to expanding the decade-old “war on terror” both within the United States and abroad.

Sidestepping the bothersome question of how to define the nebulous concept of “terrorism,” both of these bills effectively authorized an unending policy of war abroad and police-state measures at home with no basis in constitutional or international law.

One of the bills overwhelmingly passed by Congress on Thursday extends controversial provisions of the Patriot Act without additional privacy protections.

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), a member of the Senate Select Intelligence Committee warned that the law not only violates the constitution, but that the Administration relies on secret legal interpretations that allow authorities to go well beyond the language of the law.

As Wyden said on the Senate floor, “I want to deliver a warning this afternoon: When the American people find out how their government has secretly interpreted the Patriot Act, they will be stunned and they will be angry.”

The other bill passed by Congress on Thursday provides blanket authorization for the president to “use all necessary and appropriate force” against terrorists anywhere around the world “until the termination of hostilities,” providing no indication of when the hostilities might end.

The $690 billion defense authorization bill for fiscal year 2012 not only fully funds operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, it also limits President Obama’s ability to deal with Guantanamo detainees and to reduce the number of nuclear weapons – as agreed to by the United States and Russia in the New START Treaty.

The legislation limits how nuclear arms reductions mandated by the treaty with Russia can be implemented, and restricts the administration’s ability to cut nuclear weapons below levels set by the accord. Effectively, the bill renegs on agreements made with the Russian Federation on nuclear arms reduction.

As if these breaches of international norms were not enough, Congress threw another measure into the defense authorization bill: an open-ended endorsement for the executive branch to wage perpetual worldwide war, on a whim, with no further authorization from Congress required.

Specifically, the legislation provides “affirmation of [the] armed conflict with al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and associated forces.”

In Section 1034 of the defense authorization bill,

Congress affirms that–

(1) the United States is engaged in an armed conflict with al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and associated forces and that those entities continue to pose a threat to the United States and its citizens, both domestically and abroad;

(2) the President has the authority to use all necessary and appropriate force during the current armed conflict with al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and associated forces pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (Public Law 107-40; 50 U.S.C. 1541 note);

(3) the current armed conflict includes nations, organization, and persons who–

(A) are part of, or are substantially supporting, al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or associated forces that are engaged in hostilities against the United States or its coalition partners; or

(B) have engaged in hostilities or have directly supported hostilities in aid of a nation, organization, or person described in subparagraph (A); and

(4) the President’s authority pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (Public Law 107-40; 50 U.S.C. 1541 note) includes the authority to detain belligerents, including persons described in paragraph (3), until the termination of hostilities.

President Obama had threatened to veto the legislation, citing concerns over the worldwide war provision and restrictions on the executive branch’s authority to transfer terrorism suspects to the United States for prosecution or for release to other countries.

But this is unlikely, as any such veto would be highly problematic, considering the political and economic significance of the legislation. Any veto of a defense spending authorization bill would be portrayed as withdrawing support for American troops abroad, and would be unpopular among defense contractors and the employees who work for them.

From an international law perspective, however, the legislation raises all sorts of other issues, especially regarding the sovereignty and territorial integrity of countries around the world who may be accused of “substantially supporting, al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or associated forces.”

As Defense Secretary Robert Gates has stated, the movement known as “al-Qaeda” has “metastasized.”

In a November 2010 interview, Gates said, “As we’ve brought pressure on al Qaeda in North Waziristan [in Pakistan], the terrorist movement has metastasized in many ways. So now we see them in Somalia, in Yemen, in North Africa.”

So, as explained by the Secretary of Defense, as the U.S. puts pressure on al-Qaeda in one place, the movement just pops up somewhere else, sort of like a never-ending whack-a-mole game, with Predator Drones. Now, this never-ending game has been authorized by Congress, which even threw the language of “associated forces” into the legislation in case the ill-defined war against the al-Qaeda/Taliban enemy was not vague enough.

As the ACLU describes it,

The House just passed the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), including a provision to authorize worldwide war, which has no expiration date and will allow this president — and any future president — to go to war anywhere in the world, at any time, without further congressional authorization. The new authorization wouldn’t even require the president to show any threat to the national security of the United States. The American military could become the world’s cop, and could be sent into harm’s way almost anywhere and everywhere around the globe.

In authorizing unending global war against an enemy as murky as “al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or associated forces,” U.S. lawmakers have made clear that the niceties of international law are not high among Congress’s priorities.

After all, if legally binding international agreements had played some role in Congress’s deliberations, perhaps the lawmakers would have considered the possibility that authorizing “all necessary and appropriate force” against “nations, organization[s], and persons who … are substantially supporting, al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or associated forces,” might violate the UN Charter, which states that,

The Organization and its Members, in pursuit of the Purposes stated in Article 1, shall act in accordance with the following Principles.

The Organization is based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its Members.

All Members, in order to ensure to all of them the rights and benefits resulting from membership, shall fulfill in good faith the obligations assumed by them in accordance with the present Charter.All Members shall settle their international disputes by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security, and justice, are not endangered.

All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.

Congress’s declaration of perpetual worldwide war violates that Charter – ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1945 – both in principle and in spirit.

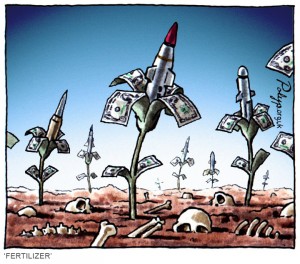

Obama’s Middle East ‘reset’ speech: A visual response

Today, President Barack Obama gave what was billed as a historic speech charting a new course for U.S. policy towards North Africa, the Middle East and the Arab world at large.

What follows is a pictorial response.

For six months, we have witnessed an extraordinary change taking place in the Middle East and North Africa. Square by square, town by town, country by country, the people have risen up to demand their basic human rights. Two leaders have stepped aside. More may follow. And though these countries may be a great distance from our shores, we know that our own future is bound to this region by the forces of economics and security, by history and by faith.

Today, I want to talk about this change — the forces that are driving it and how we can respond in a way that advances our values and strengthens our security.

There are times in the course of history when the actions of ordinary citizens spark movements for change because they speak to a longing for freedom that has been building up for years. In America, think of the defiance of those patriots in Boston who refused to pay taxes to a King, or the dignity of Rosa Parks as she sat courageously in her seat.

So it was in Tunisia, as that vendor’s act of desperation tapped into the frustration felt throughout the country. Hundreds of protesters took to the streets, then thousands. And in the face of batons and sometimes bullets, they refused to go home — day after day, week after week — until a dictator of more than two decades finally left power.

The question before us is what role America will play as this story unfolds. For decades, the United States has pursued a set of core interests in the region: countering terrorism and stopping the spread of nuclear weapons; securing the free flow of commerce and safe-guarding the security of the region; standing up for Israel’s security and pursuing Arab-Israeli peace.

We believe that no one benefits from a nuclear arms race in the region, or al Qaeda’s brutal attacks.

We believe people everywhere would see their economies crippled by a cut-off in energy supplies. As we did in the Gulf War, we will not tolerate aggression across borders, and we will keep our commitments to friends and partners.

Yet we must acknowledge that a strategy based solely upon the narrow pursuit of these interests will not fill an empty stomach or allow someone to speak their mind. Moreover, failure to speak to the broader aspirations of ordinary people will only feed the suspicion that has festered for years that the United States pursues our interests at their expense.

Given that this mistrust runs both ways — as Americans have been seared by hostage-taking and violent rhetoric and terrorist attacks that have killed thousands of our citizens — a failure to change our approach threatens a deepening spiral of division between the United States and the Arab world.

And that’s why, two years ago in Cairo, I began to broaden our engagement based upon mutual interests and mutual respect. I believed then — and I believe now — that we have a stake not just in the stability of nations, but in the self-determination of individuals. The status quo is not sustainable.

Societies held together by fear and repression may offer the illusion of stability for a time, but they are built upon fault lines that will eventually tear asunder.

So we face a historic opportunity. We have the chance to show that America values the dignity of the street vendor in Tunisia more than the raw power of the dictator. There must be no doubt that the United States of America welcomes change that advances self-determination and opportunity. Yes, there will be perils that accompany this moment of promise. But after decades of accepting the world as it is in the region, we have a chance to pursue the world as it should be.

The United States opposes the use of violence and repression against the people of the region.

The United States supports a set of universal rights. And these rights include free speech, the freedom of peaceful assembly, the freedom of religion, equality for men and women under the rule of law, and the right to choose your own leaders — whether you live in Baghdad or Damascus, Sanaa or Tehran.

Let me be specific. First, it will be the policy of the United States to promote reform across the region, and to support transitions to democracy.

That effort begins in Egypt and Tunisia, where the stakes are high — as Tunisia was at the vanguard of this democratic wave, and Egypt is both a longstanding partner and the Arab world’s largest nation. Both nations can set a strong example through free and fair elections, a vibrant civil society, accountable and effective democratic institutions, and responsible regional leadership. But our support must also extend to nations where transitions have yet to take place.

Unfortunately, in too many countries, calls for change have thus far been answered by violence. The most extreme example is Libya, where Muammar Qaddafi launched a war against his own people, promising to hunt them down like rats. As I said when the United States joined an international coalition to intervene, we cannot prevent every injustice perpetrated by a regime against its people, and we have learned from our experience in Iraq just how costly and difficult it is to try to impose regime change by force — no matter how well-intentioned it may be.

But if America is to be credible, we must acknowledge that at times our friends in the region have not all reacted to the demands for consistent change — with change that’s consistent with the principles that I’ve outlined today. That’s true in Yemen, where President Saleh needs to follow through on his commitment to transfer power. And that’s true today in Bahrain.

Bahrain is a longstanding partner, and we are committed to its security. We recognize that Iran has tried to take advantage of the turmoil there, and that the Bahraini government has a legitimate interest in the rule of law.

For decades, the conflict between Israelis and Arabs has cast a shadow over the region. For Israelis, it has meant living with the fear that their children could be blown up on a bus or by rockets fired at their homes, as well as the pain of knowing that other children in the region are taught to hate them. For Palestinians, it has meant suffering the humiliation of occupation, and never living in a nation of their own. Moreover, this conflict has come with a larger cost to the Middle East, as it impedes partnerships that could bring greater security and prosperity and empowerment to ordinary people.

As for security, every state has the right to self-defense, and Israel must be able to defend itself — by itself — against any threat. Provisions must also be robust enough to prevent a resurgence of terrorism, to stop the infiltration of weapons, and to provide effective border security. The full and phased withdrawal of Israeli military forces should be coordinated with the assumption of Palestinian security responsibility in a sovereign, non-militarized state. And the duration of this transition period must be agreed, and the effectiveness of security arrangements must be demonstrated.

Not every country will follow our particular form of representative democracy, and there will be times when our short-term interests don’t align perfectly with our long-term vision for the region.

The United States supports a set of universal rights. And these rights include free speech, the freedom of peaceful assembly, the freedom of religion, equality for men and women under the rule of law, and the right to choose your own leaders — whether you live in Baghdad or Damascus, Sanaa or Tehran.

For the American people, the scenes of upheaval in the region may be unsettling, but the forces driving it are not unfamiliar.

Our own nation was founded through a rebellion against an empire. Our people fought a painful Civil War that extended freedom and dignity to those who were enslaved. And I would not be standing here today unless past generations turned to the moral force of nonviolence as a way to perfect our union — organizing, marching, protesting peacefully together to make real those words that declared our nation: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

Libya, the ICC and America’s aggressive wars

Almost like clockwork, as the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, announced yesterday that he would seek an arrest warrant for Muammar Gaddafi, the U.S./NATO alliance intensified its bombing campaign against the beleaguered North African nation.

Crowds in Tripoli gathered Tuesday morning outside two burning buildings, the aftermath of what a Libyan official said were NATO airstrikes on government facilities. Spokesman Musa Ibrahim said the buildings housed the Ministry of Popular Inspection and Oversight – a government anti-corruption body – and the head of the police force in Tripoli.

“Is this NATO’s protection of civilians or terrifying civilians,” a Gaddafi loyalist asked CNN reporters. “This is a civilian neighborhood. … Residents are terrified.”

The attack coincides with a Russian-led initiative in which Libyan authorities have demonstrated willingness to reach a peaceful conclusion to the hostilities.

Following a meeting today with Libyan officials, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that Libya was prepared to meet all the conditions of a UN resolution calling for a ceasefire in the country’s civil war.

“Tripoli has promised to meet in full all conditions set out by the United Nations,” Lavrov said. “We were told that Tripoli is ready to consider all means … to end the conflict.”

Lavrov restated Russia’s calls for a ceasefire. “Russia is very keen to see a rapid end to the bloodshed in Libya,” Lavrov said yesterday. “We have made it clear that we are ready to support any regional and international efforts that can achieve this.”

Yet, despite the Libyan government’s reiteration of its calls for a ceasefire in line with the African Union’s roadmap for peace, which calls for cooperation in opening channels for humanitarian aid and starting a dialogue between the rebels and the government, the U.S./NATO forces appear uninterested in a political compromise.

As RIA Novosti reported yesterday,

Colonel Milad Hussein al-Fiqhi, spokesman for the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi’s forces, was killed on Sunday in a NATO raid that targeted an intelligence headquarters in the capital Tripoli, Al Arabiya television reported. …

The Libyan state news agency said on Sunday that the recent NATO airstrikes again led to civilian casualties.

The uncompromising stance the U.S. is taking against Libya, may – ironically – have its roots in an institution that just a few years ago was considered by the United States a grave threat to its global hegemony, the International Criminal Court.

Despite U.S. opposition, on April 11, 2002, the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court was ratified by enough countries to make the court a reality. “In refusing to sign the ICC treaty at the Rome Conference,” FindLaw wrote in 2002, “the U.S. found itself quite isolated.”

Only China, Iraq, Qatar, Yemen, Israel, and Libya joined in boycotting the court, while 120 nations voted in its favor.

Reacting hostilely to the Rome Statute’s ratification, President George W. Bush reiterated his opposition to the ICC and repudiated President Clinton’s decision to sign the accord.

“The United States has no legal obligations arising from its signature on Dec. 31, 2000,” the Bush administration said in a May 6, 2002 letter to U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan. “The United States requests that its intention not to become a party … be reflected in the depositary’s status lists relating to this treaty.”

With strong administration support, House Republicans promoted a bill that would allow U.S. armed forces to invade the Hague, Netherlands, where the court would be located, to rescue U.S. soldiers if they are ever prosecuted for war crimes.

But now, a decade later, it appears that the U.S. is utilizing the court that it once disparaged to help legitimize its intensifying attacks against Libya.

As the Christian Science Monitor reports today,

The potential that the International Criminal Court (ICC) could issue an arrest warrant for Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi … could give NATO more latitude to target the dictator directly.

So far, NATO airstrikes have focused on military targets – this morning they hit two government buildings in Tripoli, including the Interior Ministry. However, the head of Britain‘s military said on Sunday that NATO needed authorization to also strike infrastructure targets. There is speculation that the ICC warrants could justify NATO efforts to target Qaddafi, rather than simply to ‘protect Libyan civilians under threat of attack.’

So, how did the United States’ vociferous opposition to the ICC metamorphose into a whole-hearted endorsement of its prosecution of an officially designated U.S. enemy, in this case Muammar Gaddafi? How could the U.S. possibly use this international institution that it has opposed over the past decade towards its own ends, namely bombing Libya into submission?

The answer lies in the fact that under President Barack Obama, the U.S. took a new approach to the ICC. Rather than shunning it outright, the United States decided that it would be more effective to manipulate the Court towards its own ends.

When asked last year, following the ICC’s Kampala Review Conference, whether the United States would join the ICC, Harold Hongju Koh, Legal Advisor to the U.S. Department of State, faltered, saying:

I think our basic conviction is a strategy of engagement is good for the court and good for U.S. interests. We might as well start that process and make a serious effort at it, which is what we did. And as I said, the reaction was favorable. On the last day, they said, ‘We’re delighted to see a situation in which the U.S. is part of the solution for the court and not part of the problem.’

Stephen J. Rapp, U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues, followed up by saying:

It’s clear that joining the court is not on the table, as far as a U.S. decision at this time. But as you know, the United States takes a very long time to adopt international conventions and treaties, and sometimes doesn’t. I mean, it took us 40 years to ratify the Genocide Convention.

I think what we’re looking at here is how this court develops. We want to see it develop responsibly, to focus on crimes that involve truly massive intentional attacks on civilians, both in terms of the decisions made by its prosecutor on where to open investigations and also by its chambers, its trial chambers that have to decide whether, sometimes, to authorize those investigations or to issue arrest warrants.

What the U.S. delegation was primarily concerned about in this Review Conference was how the ICC might define the crime of “aggression.” In a statement to the conference, Rapp said:

The Eighth Session of the Assembly of States Parties ended without bringing its members close to resolving [the conditions that must be satisfied before the ICC can exercise jurisdiction over the crime of aggression]. Instead the session ended on a note that highlighted wide divisions, and this is not surprising. The questions the Special Working Group could not resolve after years of effort are inherently difficult and touch upon matters that have long elicited divergent answers.

And while the Special Working Group did produce a definition of the crime of aggression, key aspects of the definition are still uncertain. For example, what impact might the proposed definition, if adopted, have on the use of force that is undertaken to end the very crimes the ICC is now charged with prosecuting?

In other words, what the U.S. was asking last year, was, essentially, what if we decide to “enforce” these ICC principles – would we be subject to prosecution for war crimes?

Evidently, the answer was “no,” and so now the ICC is America’s new best friend.

U.S. reconsiders Middle East arms sales, but not over human rights concerns

After months of human rights and arms control organizations calling for the cutting of U.S. military aid to repressive regimes in the Middle East engaged in brutal crackdowns on pro-democracy movements, it appears the United States is beginning to reconsider its arms transfers to the region.

At a May 12 hearing of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, James Miller, principal deputy undersecretary of defense for policy, testified that the U.S. was looking at the long-term implications of arms trading in the Middle East, and had put some transactions on hold.

But it was clear that the concern over the arming of repressive regimes was not based on principles of human rights or international law, but rather the geopolitical reality of shifting U.S. interests in the region. With regimes on the verge of collapse, the U.S. appears to be concerned that the weapons it sells to friendly dictators may fall into the wrong hands.

In Bahrain, which hosts the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet, the Shiite majority continues to demonstrate against its lack of civil rights and its second class status in the government. The Sunni minority government has brutally repressed the demonstrations, even targeting doctors who provide medical attention to injured protesters.

Since the beginning of protests in mid-February, scores of protesters have been killed and many others have gone missing. According to opposition groups, over 800 anti-government activists, including 17 women, have been arrested.

The United Nations High Commissioner for human rights has called on Bahrain to free political prisoners and allow an independent probe into reports of torture.

“My office has also received reports of severe torture against human rights defenders who are currently in detention … There must be independent investigations of these cases of death in detention and allegations of torture,” Navi Pillay said in a statement released on May 5.

The Bahraini regime has also engaged in a campaign of cultural genocide, targeting, in particular Shiite mosques.

The U.S. provided Bahrain $19 million for the fiscal year 2010, and this fiscal year, the island monarchy is on track to receive $19.5 million in military aid.

The government in Yemen is also using excessive force to crack down on civilian protesters. More than 170 people are reported to have been killed since the unrest began in January, reports BBC, with three more added to the list on Friday.

Last Wednesday, Amnesty International called on the Yemeni authorities to stop using unnecessary deadly force against anti-government protesters.

“Security forces in Yemen must be immediately stopped from using live ammunition on unarmed protesters,” said Philip Luther, Amnesty International’s Deputy Director for the Middle East and North Africa.

Yet, according to the Congressional Research Service, the Obama administration requested $106 million in U.S. economic and military assistance for Yemen in 2011, and for 2012, it has requested $116 million in economic and military aid.

A coalition of 19 human rights groups based in the Middle East wrote on April 12,

[T]he continuation of the despotic campaign against human rights defenders and political groups that are calling for profound democratic reforms reflect complicity and lack of political will from international actors, particularly the US and EU. These actors remain to prefer securing their strategic interests in the Gulf region by choosing to sustain the political stability of repressive regimes, turn a blind eye to the people’s aspirations for democracy, and remain silent on massive and systematic human rights violations in this region of the world.

But rather than raising the issue of human rights or U.S. compliance with international law — which prohibits aid to countries that commit systematic human rights violations — Members of the House Foreign Affairs Committee expressed concern that arms sales to certain countries may no longer be advancing U.S. foreign policy interests.

At the May 12 hearing, Committee Chairwoman Ileana Ros-Lehtinen asked Ellen Tauscher, Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security at the State Department, if she can “assure this committee that arms sales proposals are based on well-formulated, focused and realistic capability requirements?”

The Chairwoman pointed to a General Accounting Office report that claims that “State and DOD did not consistently document how arms transfers to Gulf countries advanced U.S. foreign policy and national security goals.”

“Are you confident,” Ros-Lehtinen asked, “that all sales comply with U.S. conventional arms transfer policy?”

Tauscher assured the Committee that arms transfers are done in consultation with allies and with the Congress. “The answer is yes,” she said, “we are confident that arms are going where they are supposed to be going,” and do not fall into the wrong hands.

There are indications, however, that there are some changes taking place regarding arms transfers to the Middle East, in light of the ongoing rebellions in the region.

“Historic change of this magnitude will inevitably prompt us, as well as our colleagues throughout government, to reassess current policy approaches to ensure they still fit with the changing landscape,” said Andrew Shapiro, the assistant secretary at the State Department’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, in a May 3 speech.

He went on to say,

It is important to emphasize that arms transfers are a tool to advance U.S. foreign policy. And therefore when U.S. foreign policy interests, goals, and objectives shift, evolve, and transform over time, so will our arms transfer policy.

In the current dynamic geopolitical environment, it is natural that we take a look at our policies and approaches. For instance, we in PM are taking a close look at the Conventional Arms Transfer policy. This policy has suited the United States well since it was enacted just after the end of the Cold War. But it is time to dust off its pages and make sure that it reflects the reality of today. We don’t know yet what specific changes, if any, are needed. But in light of sweeping transformation it is essential that we, as well as our colleagues in other government agencies, assess current processes and procedures toward the region. We simply cannot operate as if it’s business as usual. U.S. foreign policy is not immune to geopolitical change and therefore neither is U.S. arms transfer policy.

It is enlightening that Shapiro and others are highlighting the importance of complying with the Conventional Arms Transfer policy, but remaining silent on the requirement of this policy to ensure that arms transfers are consistent with international agreements and arms control initiatives.

The Conventional Arms Transfer policy also requires the U.S. to consider “the human rights, terrorism and proliferation record of the recipient and the potential for misuse of the export in question.”

According to the International Law Commission (ILC), the official UN body that codifies customary international law,

A State which aids or assists another State in the commission of an internationally wrongful act by the latter is internationally responsible for doing so if: (a) that State does so with knowledge of the circumstances of the internationally wrongful act; and (b) the act would be internationally wrongful if committed by that State” (Article 16 of the International Law Commission, “Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts,” (2001) which were commended by the General Assembly, A/RES/56/83).

Further, the U.S. Foreign Assistance Act stipulates that “no security assistance may be provided to any country the government of which engages in a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights” and the Arms Export Control Act authorizes the supply of U.S. military equipment and training only for lawful purposes of internal security, “legitimate self-defense,” or participation in UN peacekeeping operations or other operations consistent with the UN Charter.

As the Arms Control Association reported on March 31, of the 28 countries for which Congress was notified of foreign military sales last year, according to the State Department’s own human rights reports, more than a third (11) of the states “failed to guarantee freedom of speech, association, and assembly, as well as a free press.” Further, torture, arbitrary arrest, and discrimination remained a problem in many of these same states. (Spreadsheet and further explanation available here.)

As Congress begins to scrutinize U.S. arms transfers in light of the political changes in the Middle East, the human rights and international law dimension should be part of the equation. But it is clear that the last thing on anyone’s mind is how U.S. policy conforms with human rights standards, even as unthinkable atrocities unfold in countries like Bahrain and Yemen.

With the profound changes taking place in the Middle East, it is sobering to realize that the only change we can expect in the USA is which thuggish regime we might be arming next week in the advancement of “U.S. national interests.”

Amnesty’s new report details serious violations of human rights in the USA

In its annual report on the state of human rights around the world released Friday, Amnesty International slammed the United States for its continued application of the death penalty, police brutality, substandard prison conditions, arbitrary detention at Guantanamo and Bagram airbase, and a culture of impunity for officials who have authorized torture.

“Forty-six people were executed during the year,” Amnesty’s introduction for the U.S. country report begins, “and reports of excessive use of force and cruel prison conditions continued.”

Further,

Scores of men remained in indefinite military detention in Guantánamo as President Obama’s one-year deadline for closure of the facility there came and went. Military commission proceedings were conducted in a handful of cases, and the only Guantánamo detainee so far transferred to the US mainland for prosecution in a federal court was tried and convicted. Hundreds of people remained held in US military custody in the US detention facility on the Bagram airbase in Afghanistan. The US authorities blocked efforts to secure accountability and remedy for crimes under international law committed against detainees previously subjected to the USA’s secret detention and rendition programme.

Amnesty notes that despite President Obama’s promise to close the Guantánamo detention facility by January 22, 2010, 198 detainees were still held there, about half of them Yemeni nationals. By the end of the year, 174 men were still being held, “including three who had been convicted under a military commission system which failed to meet international fair trial standards.”

In April, Amnesty notes, the Pentagon released the rules governing military commission proceedings, which confirmed that the Obama administration reserves the right to continue to detain individuals indefinitely even if they were acquitted by a military commission.

On the issue of impunity, the report observes:

There continued to be an absence of accountability and remedy for the human rights violations, including the crimes under international law of torture and enforced disappearance, committed as part of the USA’s programme of secret detention and rendition (transfer of individuals from the custody of one state to another by means that bypass judicial and administrative due process) operated under the administration of President George W. Bush.

In his memoirs, published in November, and in a pre-publication interview, former President Bush admitted that he had personally authorized “enhanced interrogation techniques” for use by the CIA against detainees held in secret custody. One of the techniques he said he authorized was “water-boarding”, a form of torture in which the process of drowning a detainee is begun.

On 9 November, the US Department of Justice announced, without further explanation, that no one would face criminal charges in relation to the destruction in 2005 by the CIA of videotapes made of the interrogations of two detainees – Abu Zubaydah and ‘Abd al-Nashiri – held in secret custody in 2002. The 92 tapes depicted evidence of the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques”, including “water-boarding”, against the two detainees.

The “preliminary review” ordered in August 2009 by Attorney General Eric Holder into some aspects of some interrogations of some detainees held in the secret detention programme was apparently continuing at the end of the year.

Excessive use of force by the police continued to be a problem, with 55 people being killed by police Tasers, which are marketed as “non-lethal weapons.” Amnesty notes that “most of the deceased were unarmed and did not appear to present a serious threat when they were shocked, in some cases multiple times.”

Prison conditions were also a cause for concern, with complaints, in particular, of the authorities’ cruel usage of long-term isolation in super-maximum security units.

Amnesty also highlighted the case of the “Cuban Five,” who were convicted in 2001 of acting as intelligence agents for Cuba and related charges. The five men were involved in monitoring the actions of Miami-based terrorist groups, and are now serving four life sentences and 75 years collectively.

In June, Amnesty International reports, a new appeal was filed in the case of Gerardo Hernández, one of the Cuban Five. The appeal was based, in part, on evidence that the U.S. government had secretly paid journalists to write prejudicial articles in the media at the time of trial, thereby undermining the defendants’ due process rights.

In October, Amnesty International sent a report to the Attorney General outlining the organization’s concerns in the case of the Cuban Five. Specifically, Amnesty said that “there were doubts about the fairness and impartiality of the trial which have not been resolved on appeal.”

Regarding the death penalty, Amnesty highlighted the case of Anthony Graves, who was released in Texas, 16 years after he was sentenced to death. “A new trial had been ordered by a federal court in 2006,” Amnesty points out, “but charges were dismissed in October after the prosecution found no credible evidence linking him to the 1992 crime. He became the 138th person to be released from death row in the USA since 1973 on grounds of innocence.”

Nevertheless, another 1,234 executions have been carried out since the U.S. Supreme Court lifted a moratorium on the death penalty in 1976, with 46 added to the list last year.

We are different: American exceptionalism and international norms

Over the past couple months, President Barack Obama has been touching on a certain theme, namely that Americans are different than the rest of the world’s people, that somehow, Americans are special. In short, America is exceptional.

In explaining the U.S. intervention in the Libyan civil war, for example, Obama said on March 28,

To brush aside America’s responsibility as a leader and — more profoundly — our responsibilities to our fellow human beings under such circumstances would have been a betrayal of who we are. Some nations may be able to turn a blind eye to atrocities in other countries. The United States of America is different.

After committing the United States to war in Libya, the President then ordered the assassination of Osama bin Laden.

In responding to skepticism that naturally followed after the U.S. allegedly killed bin Laden and then dumped his body into the sea — without allowing any outside independent observers to confirm that it was him — President Obama said that his decision “is something that makes us different.”

CBS reporter Steve Kroft asked Obama if it was his decision to dump the body at sea, and Obama replied that it was actually a joint decision.

“We thought it was important to think through ahead of time how we would dispose of the body if he were killed in the compound,” said the president.

Obama went on: “Frankly we took more care on this than, obviously, bin Laden took when he killed 3,000 people. He didn’t have much regard for how they were treated and desecrated. But that, again, is somethin’ that makes us different. And I think we handled it appropriately.”

It is interesting and revealing that the President of the United States is comparing his own actions against those of an internationally wanted terrorist. We took more care in killing bin Laden, says Obama, than bin Laden did, when he killed 3,000 Americans.

But of course, the U.S. can’t show the pictures of a dead bin Laden in order to quell the growing doubts about his death, because that would be barbaric, and in fact, not showing the pictures “makes us different,” it makes us special, or exceptional.

American exceptionalism is the idea that the United States is somehow different from other nations. Stemming from its emergence from a revolution against illegitimate monarchy, and developing a unique ideology based on liberty and equality, America has long used its underdog status to justify whatever it wants to do.

As Michael Ignatieff puts it in American Exceptionalism and Human Rights,

Since 1945 America has displayed exceptional leadership in promoting international human rights. At the same time, however, it has also resisted complying with human rights standards at home or aligning its foreign policy with these standards abroad. Under some administrations, it has promoted human rights as if they were synonymous with American values, while under others, it has emphasized the superiority of American values over international standards. This combination of leadership and resistance is what defines American human rights behavior as exceptional, and it is this complex and ambivalent pattern that the book seeks to explain.

Thanks to Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt, the United States took a leading role in the creation of the United Nations and the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. …

The same U.S. government, however, has also supported rights-abusing regimes from Pinochet’s Chile to Suharto’s Indonesia; sought to scuttle the International Criminal Court, the capstone of an enforceable global human rights regime; maintained practices–like capital punishment–at variance with the human rights standards of other democracies; engaged in unilateral preemptive military actions that other states believe violate the UN Charter; failed to ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women; and ignored UN bodies when they criticized U.S. domestic rights practices.

What is exceptional here is not that the United States is inconsistent, hypocritical, or arrogant. Many other nations, including leading democracies, could be accused of the same things. What is exceptional, and worth explaining, is why America has both been guilty of these failings and also been a driving force behind the promotion and enforcement of global human rights. What needs explaining is the paradox of being simultaneously a leader and an outlier.

Lately, the U.S. has been more of an outlier than a leader. Through unlawful drone attacks, through commando raids that violate nations’ sovereignty, through ongoing indefinite detentions of terrorist suspects at Guantanamo, the USA has proved time and again that its concern over the niceties of international law runs only skin deep.

International law matters only when the United States can use it to its advantage, which is what really “makes us different.” The law doesn’t apply to us, in other words.

On OBL, Gaddafi, assassinations, and the remnants of international law

After nearly ten years of fighting in Afghanistan and eight years of occupying Iraq, Americans seem more than willing to forget everything they might have learned since Sept. 11, 2001, and gladly accept the government’s story that Special Forces took out the #1 American nemesis in a midnight raid – the stuff of legend, made for Hollywood movies and late-night TV.

If we are to believe what the U.S. government tells us about its purported commando attack on Osama bin Laden over the weekend, we are expected to rejoice over the extrajudicial killing of a suspect in one of the greatest crimes ever committed against the American people.

The alleged killing of bin Laden by U.S. Special Forces means that there will never be a trial in a court of law to prove bin Laden’s complicity in the murder of nearly 3,000 Americans, and many other individuals of various nationalities.

Assuming for a moment that the government’s story is true, what we are talking about here is an extrajudicial killing in violation of international law.

As the Harvard Law Review pointed out in a 2006 article:

Black’s Law Dictionary defines assassination as ‘the act of deliberately killing someone especially a public figure, usually for hire or for political reasons.’ If termed ‘assassination,’ then attacks on leaders have been construed as prohibited by Article 23b of the Hague Convention of 1899, which outlaws ‘treacherous’ attacks on adversaries, and by the Protocol Addition to the Geneva Convention of 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflict (Protocol I), which prohibits attacks that rely on ‘perfidy.’

For the reasons laid out in international law, the U.S. and Israel have abandoned the use of the word “assassination,” and adopted the more politically correct “targeted killing.”

[E]specially since the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Israel and the United States have reframed such actions as ‘targeted killings,’ defining the victims as ‘enemy combatants’ who are therefore legitimate targets wherever they are found. This redefinition has relied on and benefited from the work of some in the international law community who have long argued that in some instances, targeted attacks on leaders are not prohibited by international law. This reinterpretation of law is not a radical shift; the radical shift is US and Israeli willingness to engage in attacks openly, whatever may have occurred covertly in the past decades.

But the change in terminology does not indicate a change in the law, which prohibits extrajudicial executions, including state-sponsored assassinations, and requires that even the worst criminals be granted due process and fair trials.

Regardless, it should be remembered that following the heinous attack of Sept. 11, 2001, Afghanistan’s Taliban government offered to hand over the alleged mastermind, Osama bin Laden, to a third country. As the Guardian reported on Oct. 14, 2001,

The Taliban would be ready to discuss handing over Osama bin Laden to a neutral country if the US halted the bombing of Afghanistan, a senior Taliban official said today.

Afghanistan’s deputy prime minister, Haji Abdul Kabir, told reporters that the Taliban would require evidence that Bin Laden was behind the September 11 terrorist attacks in the US.

‘If the Taliban is given evidence that Osama bin Laden is involved” and the bombing campaign stopped, “we would be ready to hand him over to a third country’, Mr Kabir added.

But the U.S., for whatever reason, was unwilling to entertain this offer, or to provide evidence of bin Laden’s complicity in the 9/11 attacks. Instead, the U.S. government insisted on launching wars that in Iraq and Afghanistan that have killed hundreds of thousands of civilians and cost the American taxpayer upwards of a trillion dollars.

Now, by purportedly killing the alleged mastermind of 9/11 without the benefit of a trial, the U.S. is still not compelled to produce any evidence of bin Laden’s guilt.

Coincidentally, perhaps, the extrajudicial killing of bin Laden falls just on the heels of the botched assassination attempt of Muammar Gaddafi. While failing to kill the leader of Libya, the U.S./NATO strike on Tripoli did manage to kill Gaddafi’s son, and three of his young grandchildren, who were still in diapers.

In response to Saturday’s attack on Gaddafi’s home, Congressman Dennis Kucinich (D-OH) made the following statement:

NATO’s leaders have blood on their hands. NATO’s airstrike seems to have been intended to carry out an illegal policy of assassination. This is a deep stain which can never fully wash. This grave matter cannot be addressed with empty words. Words will not bring back dead children. Actions must be taken to stop more innocents from getting slaughtered.

Today’s attack underscores that the Obama Doctrine of so-called humanitarian intervention appears to be a cover for regime change through assassination and murder.

These tactics are in serious violation of international law, signaling a return to the law of the jungle. By legitimizing them in the mass media through images of Americans celebrating the extrajudicial killing of an alleged murderer, the United States falls further into the abyss of lawlessness.

And this is assuming that the story told over the weekend is true – that the USA killed an internationally wanted criminal, accused of killing people of numerous nationalities, without allowing an outside source to independently verify that it was in fact Osama bin Laden who was killed, and he was in fact killed the way that the Pentagon claims. Instead, the U.S. just dumped his body in the ocean.

All of those claims are highly dubious.

![corporate_flag[4]](https://compliancecampaign.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/corporate_flag4.jpg?w=479)