Overlooking U.S. stockpile, OPCW praises Kerry for leadership on chemical weapons

Meeting today with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, Ahmet Uzumcu, the Director General of the Organization for for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, commended the United States for its “invaluable support for the ongoing mission in Syria,” but failed to highlight the U.S.’s failure to destroy its own chemical weapons stockpile.

According to an OPCW press release, the Director General “stressed that ongoing engagement by the United States at all levels will be vital to the success of the mission.” Yet, curiously, there was no mention of the fact that the United States has missed two deadlines (in 2007 and 2012) for destroying its own chemical weapons and retains thousands of tons of the banned munitions at stockpile sites in Kentucky and Colorado.

Sidestepping the U.S.’s obligations to destroy its chemical weapons, Kerry noted that 50% of the Syrian chemicals have now been removed from Syria, saying the progress is “significant, but the real significance will be when all the chemical weapons are out.”

“Regrettably,” Kerry said, “the Syrians missed a March 15th date for destruction of facilities. We have some real challenges ahead of us now in these next weeks.”

The Chemical Weapons Convention prohibits “the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons.” When it went into effect 17 years ago, the U.S. declared a huge domestic chemical arsenal of 27,771 metric tons to the OPCW.

Although it has destroyed about 90% of its chemical weapons, the U.S. still maintains a stockpile of 2,700 tons according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Nevertheless, Kerry somehow had the gall to criticize Syria for not moving more quickly towards destroying its chemical arsenal.

“We in the United States are convinced that if Syria wanted to, they could move faster,” Kerry said. “And we believe it is imperative to achieve this goal and to move as rapidly as possible because of the challenges on the ground.”

Rather than challenge Kerry for the U.S. double standard, Uzumcu praised him for gracing the OPCW with his presence.

“Mr. Secretary,” Uzumcu said,

we are very pleased to receive you here at the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. This is the first visit by a Secretary of State from the United States to our organization. We are, of course, very grateful for the continued support by the United States to the OPCW, and the latest one is the fact that in Syria we think that the success of this operation mission in Syria will further strengthen the norm against chemical weapons throughout the world. And we’ll look forward to our exchange of views today. Thank you very much.

It’s pretty remarkable that despite its flagrant violations of the Chemical Weapons Convention, the United States not only gets a pass, but is actually praised for even visiting the OPCW.

One wonders if this praise showered on the U.S. Secretary of State has anything to do with the fact that one of Uzumcu’s predecessors, José Bustani, lost his job in 2002 under U.S. pressure.

Bustani, who had just been unanimously re-elected 11 months earlier, had pushed for international chemical weapons monitors inside Iraq and thus was seen as impeding the U.S. push for war against against that country.

The U.S. accused him of “polarizing and confrontational conduct,” as well as “advocacy of inappropriate roles for the OPCW,” and called for a special session of the 145-nation chemical weapons watchdog in April 2002, at which Bustani was removed after intense U.S. lobbying.

The International Labor Organization subsequently called the decision “an unacceptable violation of the principles on which international organisations’ activities are founded …, by rendering officials vulnerable to pressures and to political change.”

Bustani was awarded €50,000 in damages, his pay for the remainder of his second term, and his legal costs.

The message, however, was sent loud and clear: do not cross the United States, or your career will suffer the consequences.

It’s hard to say for sure, but perhaps this is why the OPCW Director General now showers such praise on the U.S. government, despite its flouting of international norms against chemical weapons.

Crimea, Iraq and international law: A little perspective

The war of words between Barack Obama and Vladimir Putin has continued this week, with Obama forcefully rejecting an argument from Putin that the referendum for Crimean secession from Ukraine to become part of Russia, was “fully consistent with the norms of international law and the UN Charter.”

In a statement, the White House said that the Crimean referendum “violates the Ukrainian constitution and occurred under duress of Russian military intervention.” Obama further emphasized that “that Russia’s actions were in violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

Vice President Joe Biden weighed in on Tuesday, saying that Russia’s treaty to annex Crimea was a “blatant violation of international law” and that Russian forces had carried out a “brazen military incursion” that “ratcheted up ethnic tensions.” Russia’s annexation of Crimea was “nothing more than a land grab,” Biden said.

For those looking for evidence of how the United States routinely twists international law and concepts of sovereignty depending on its geopolitical needs and whims at a given moment, the diplomatic spat over Crimea could hardly be better timed. Today, of course, is the 11th anniversary of the unprovoked, illegal war of aggression carried out by the United States against the sovereign nation of Iraq.

Joe Biden was instrumental in building up congressional support for that ill-fated war. As then-chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he oversaw hearings which systematically excluded individuals who were critical of claims regarding Iraq’s alleged possessions of weapons of mass destruction, including former UN weapons inspector Scott Ritter.

When Biden voted in 2002 to authorize the invasion of Iraq, he falsely claimed on the Senate floor, “[Saddam Hussein] possesses chemical and biological weapons and is seeking nuclear weapons.”

With congressional authorization in hand, on March 19, 2003 (already the 20th in Iraq), President George W. Bush launched a bombing campaign of Baghdad followed by an all-out military assault which ultimately led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis and nearly 5,000 U.S. soldiers. Another 100,000 Americans have been wounded.

As staggering as those numbers may be, they don’t fully convey the magnitude of the crime which was committed by launching this war 11 years ago. The impact on international norms was equally profound, and continue to reverberate today. Russian President Putin himself cited the Iraq invasion in his address to parliament on March 18.

“Our western partners, led by the United States of America, prefer not to be guided by international law in their practical policies, but by the rule of the gun,” he said.

They have come to believe in their exclusivity and exceptionalism, that they can decide the destinies of the world, that only they can ever be right. They act as they please: here and there, they use force against sovereign states, building coalitions based on the principle “If you are not with us, you are against us.” To make this aggression look legitimate, they force the necessary resolutions from international organisations, and if for some reason this does not work, they simply ignore the UN Security Council and the UN overall.

This happened in Yugoslavia; we remember 1999 very well. It was hard to believe, even seeing it with my own eyes, that at the end of the 20th century, one of Europe’s capitals, Belgrade, was under missile attack for several weeks, and then came the real intervention. Was there a UN Security Council resolution on this matter, allowing for these actions? Nothing of the sort. And then, they hit Afghanistan, Iraq, and frankly violated the UN Security Council resolution on Libya, when instead of imposing the so-called no-fly zone over it they started bombing it too.

Regardless of what one might think of Putin’s policies — whether his domestic human rights record or his actions in Ukraine — the factual basis of his critique of U.S. foreign policy cannot be denied. While pundits and scholars may quibble over the lawfulness of theYugoslavia war, the Afghanistan invasion, or the bombing of Libya, what should be beyond dispute at this point is that the attack on Iraq was unequivocally criminal.

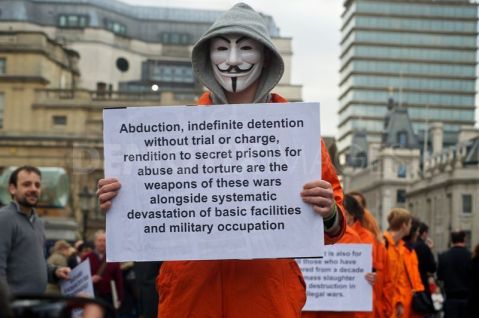

The violations of international law, which began even before the initial shock and awe bombing campaign, continued and intensified throughout the invasion, and the subsequent occupation and counterinsurgency campaign. To this date, no high-ranking officials have ever been held accountable for these actions.

Threats of Force

As early as January 2003 — three months before the U.S. actually launched its attack — the Pentagon was announcing its plans for the “shock and awe” bombing campaign.

“If the Pentagon sticks to its current war plan,” CBS News reported on January 24, “one day in March the Air Force and Navy will launch between 300 and 400 cruise missiles at targets in Iraq. … [T]his is more than the number that were launched during the entire 40 days of the first Gulf War. On the second day, the plan calls for launching another 300 to 400 cruise missiles.”

A Pentagon official warned: “There will not be a safe place in Baghdad.”

The intention of announcing these plans so early — before the UN weapons inspectors had finished their job and before diplomacy in the Security Council had been allowed to take its course — appeared to be a form of psychological warfare against the Iraqi people. If that was not the intent, it was certainly the effect.

A group of psychologists published a report in January 2003 describing the looming war’s effect on children’s mental health.

”With war looming, Iraqi children are fearful, anxious and depressed,” they found. ”Many have nightmares. And 40 percent do not think that life is worth living.”

The explicit threats being made against Iraq in early 2003 were arguably a violation of the UN Charter, which states that “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.”

Shock and Awe

“Shock and awe” began with limited bombing on March 19, 2003 as U.S. forces unsuccessfully attempted to kill Saddam Hussein. Attacks continued against a small number of targets until March 21, 2003, when the main bombing campaign began. U.S.-led forces launched approximately 1,700 air sorties, with 504 using cruise missiles.

The attack was a violation of the UN Charter, which stipulates that “Members shall settle their international disputes by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security, and justice, are not endangered.” The only exception to this is in the case of Security Council authorization, which the U.S. did not have.

Targeting Civilians

Desperate to kill Saddam Hussein, Bush ordered the bombing of an Iraqi residential restaurant on April 7. A single B-1B bomber dropped four precision-guided 2,000-pound bombs. The four bunker-penetrating bombs destroyed the target building, the al Saa restaurant block and several surrounding structures, leaving a 60-foot crater and unknown casualties.

Diners, including children, were ripped apart by the bombs. One mother found her daughter’s torso and then her severed head. U.S. intelligence later confirmed that Hussein wasn’t there.

The deliberate attack on a civilian target was in breach of the Fourth Geneva Convention’s protection of non-combatants, which states:

(1) Persons taking no active part in the hostilities, including members of armed forces who have laid down their arms and those placed hors de combat by sickness, wounds, detention, or any other cause, shall in all circumstances be treated humanely, without any adverse distinction founded on race, colour, religion or faith, sex, birth or wealth, or any other similar criteria.To this end the following acts are and shall remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever with respect to the above-mentioned persons: (a) violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture.

Failure to Provide Security

After the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime on April 9, the U.S. action in Iraq took on the character of an occupation, and as the occupying power, the U.S. was bound by international law to provide security. But in the post-war chaos, in which looting of Iraq’s national antiquities was rampant, U.S. forces stood by as Iraq’s national museum was looted and countless historical treasures were lost.

Despite the fact that U.S. officials were warned even before the invasion that Iraq’s national museum would be a “prime target for looters” by the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance (ORHA), set up to supervise the reconstruction of postwar Iraq, U.S. forces took no action to secure the building. In protest of the U.S. failure to prevent the resulting looting of historical artefacts dating back 10,000 years, three White House cultural advisers resigned.

“It didn’t have to happen”, Martin Sullivan – who chaired the President’s Advisory Committee on Cultural Property for eight years – told Reuters news agency. The UN’s cultural agency UNESCO called the loss and destruction “a disaster.”

Cluster Bombs

During the course of the war, according to a four-month investigation by USA Today, the U.S. dropped 10,800 cluster bombs on Iraq. “The bomblets packed inside these weapons wiped out Iraqi troop formations and silenced Iraqi artillery,” reported USA Today. “They also killed civilians. These unintentional deaths added to the hostility that has complicated the U.S. occupation.”

U.S. forces fired hundreds of cluster weapons into urban areas from late March to early April, killing dozens and possibly hundreds of Iraqi civilians. The attacks left behind thousands of unexploded bomblets that continued to kill and injure civilians weeks after the fighting stopped.

Because of the indiscriminate effect of these duds that keep killing long after the cessation of hostilities, the use of cluster munitions is banned by the international Convention on Cluster Munitions, which the United States has refused to sign.

Authorizing Torture

Possibly anticipating a drawn-out occupation and counter-insurgency campaign in Iraq, in a March 2003 memorandum Bush administration lawyers devised legal doctrines justifying certain torture techniques, offering legal rationales “that could render specific conduct, otherwise criminal, not unlawful.”

They argued that the president or anyone acting on the president’s orders are not bound by U.S. laws or international treaties prohibiting torture, asserting that the need for “obtaining intelligence vital to the protection of untold thousands of American citizens” supersedes any obligations the administration has under domestic or international law.

“In order to respect the President’s inherent constitutional authority to manage a military campaign,” the memo states, U.S. prohibitions against torture “must be construed as inapplicable to interrogations undertaken pursuant to his Commander-in-Chief authority.”

Over the course of the next year, disclosures emerged that torture had been used extensively in Iraq for “intelligence gathering.” Investigative journalist Seymour Hersh disclosed in The New Yorker in May 2004 that a 53-page classified Army report written by Gen. Antonio Taguba concluded that Abu Ghraib prison’s military police were urged on by intelligence officers seeking to break down the Iraqis before interrogation.

“Numerous incidents of sadistic, blatant and wanton criminal abuses were inflicted on several detainees,” wrote Taguba.

These actions, authorized at the highest levels, constituted serious breaches of international and domestic law, including the Convention Against Torture, the Geneva Convention relative to the treatment of Prisoners of War, as well as the U.S. War Crimes Act and the Torture Statute.

Supporting Death Squads

As part of its counterinsurgency campaign, the United States also played a key role in training and overseeing U.S.-funded special police commandos who ran a network of torture centers in Iraq and engaged in a brutal sectarian civil war.

A 15-month investigation by the Guardian and BBC Arabic revealed how retired U.S. colonel James Steele, a veteran of American dirty wars in El Salvador and Nicaragua, and another special forces veteran, Colonel James Coffman, worked with Steele and reported directly to General David Petraeus, who had been sent into Iraq to organize the Iraqi security services.

As the Guardian reported last year:

The Pentagon sent a US veteran of the “dirty wars” in Central America to oversee sectarian police commando units in Iraq that set up secret detention and torture centres to get information from insurgents. These units conducted some of the worst acts of torture during the US occupation and accelerated the country’s descent into full-scale civil war. …

The allegations, made by US and Iraqi witnesses in the Guardian/BBC documentary, implicate US advisers for the first time in the human rights abuses committed by the commandos. It is also the first time that Petraeus – who last November was forced to resign as director of the CIA after a sex scandal – has been linked through an adviser to this abuse.

(The full hour-long documentary can be seen here.)

While there had long been allegations that the U.S. was involved in fueling the sectarian violence as a way to curtail the Iraqi resistance to the U.S. occupation through classic divide-and-conquer techniques, the Guardian investigation is the first conclusive evidence that the U.S. was in fact involved in supporting the violence. At its height, the sectarian civil war between Shia and Sunni was claiming 3,000 victims a month.

Other Crimes

These are just a few of the more blatant examples U.S. violations of international law from the earliest days of the invasion of Iraq, for which no one has been held to account. There are of course, many others that we know about and others that we don’t.

There was the 2004 assault on Fallujah in which white phosphorus – banned under international law – was used against civilians. There was the 2005 Haditha massacre, in which 24 unarmed civilians were systematically murdered by U.S. marines.

And of course, there was the 2007 “Collateral Murder” massacre revealed by WikiLeaks in 2010 (for which the only person to be punished is the courageous whistleblower who brought it to light).

While each of the above-mentioned crimes should be dealt with individually, it is important to remember the words of American prosecutor Robert Jackson, who led the prosecutions of Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg. In his opening statement before the international military tribunal on Nazi war crimes, Jackson denounced aggressive war as “the greatest menace of our time.”

Jackson noted that “to start an aggressive war has the moral qualities of the worst of crimes.” The tribunal, he said, had decided that “to initiate a war of aggression … is not only an international crime: it is the supreme international crime differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of whole.”

When it comes to Iraq, the accumulated evil of the whole is difficult to fully comprehend. Even now, 11 years after the initial U.S. invasion, the country is reeling from daily suicide bombings and sectarian violence, and an ongoing refugee crisis. According to Refugees International, Iraqi internally displaced persons number roughly 2.8 million.

“Internally displaced Iraqis are extremely vulnerable and live in constant fear, with limited access to shelter, food, and basic services,” notes the NGO.

As Al Jazeera reporter Dahr Jamail, who was one of the few unembedded journalists to report extensively from Iraq during the 2003 Iraq invasion, describes it, the reality in Iraq is “utter devastation.” He said on Democracy Now after returning from a trip to Iraq last year:

It’s a situation where, overall, we can say that Iraq is a failed state. The economy is in a state of crisis, perpetual crisis, that began far back with the institution of the 100 Bremer orders during—under the Coalition Provisional Authority, the civil government set up to run Iraq during the first year of the occupation. And it’s been in crisis ever since.

The average Iraqi is just barely getting by. And how can they get by when there’s virtually no security across much large swaths of country to this day, where, you know, as we see in the headlines recently, even when there’s not these dramatic, spectacular days of dozens of people being killed by bombs across Baghdad and other parts of Iraq, on any given day there’s assassinations, there’s detentions, there’s abductions and people being disappeared and kidnapped?

There is also the tragic legacy of cancer and birth defects caused by the U.S. military’s extensive use of depleted uranium and white phosphorus in Iraq. Noting the birth defects in the Iraqi city of Fallujah, Jamail says:

They’re extremely hard to bear witness to. But it’s something that we all need to pay attention to … What this has generated is, from 2004 up to this day, we are seeing a rate of congenital malformations in the city of Fallujah that has surpassed even that in the wake of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that nuclear bombs were dropped on at the end of World War II.

Still pressing for justice 11 years after the launching of this criminal war, several organizations, including Iraq Veterans Against the War, the Organization of Women’s Freedom in Iraq, the Federation of Workers Councils and Unions in Iraq, and the Center for Consitutional Rights, have launched the “right to heal” campaign.

The network of Iraqis and U.S. military veterans came together last year to hold the U.S. government accountable for the lasting effects of war and the rights of veterans and civilians to heal.

“The Iraq war is not over for Iraqi civilians and U.S. veterans who continue to struggle with various forms of trauma and injury,” says the Right to Heal website, “for Iraqis and veterans who suffer the effects of environmental poisoning due to certain U.S. munitions and burn pits of hazardous material; and for a growing generation of orphans and people displaced by war.”

The groups are working to highlight the lack of accountability for the ongoing human rights violations of Iraqis, Afghans, and U.S. military veterans, and on March 26 are holding a People’s Hearing on the Lasting Impact of the Iraq War.

Moderated by Phil Donahue, former host of The Phil Donahue Show and Co-Director of the film Body of War, the People’s Hearing will include Iraqi civil society leaders and U.S. military veterans who will testify to the lasting impact of the war and make the case that the U.S. government must be held to account for the serious damage it has caused.

Another effort for accountability is playing out in the courts.

On March 18, the Center for Constitutional Rights urged a federal appeals court to re-open a case brought by four Iraqi Abu Ghraib torture victims against private military contractor CACI Premier Technology, Inc. The men were subjected to sexual violence, electric shocks, forced nudity, broken bones, and deprivation of oxygen, food, and water.

U.S. military investigators concluded that several CACI interrogators directed U.S. soldiers to commit “sadistic, blatant, and wanton criminal abuses” of Abu Ghraib detainees in order to “soften” them up for interrogations, but a district court judge dismissed the case against CACI in June by narrowly interpreting the Supreme Court’s decision in Kiobel v. Shell/Royal Dutch Petroleum to foreclose Alien Tort Statute (ATS) claims arising in Iraq.

Said Center for Constitutional Rights Legal Director Baher Azmy, “U.S. courts must at last provide a remedy for the victims of torture at Abu Ghraib. CACI indisputably played a key role in those atrocities, and it is time for them to be held accountable. The lower court’s ruling creates lawless spaces where corporations can commit torture and war crimes and then find safe haven in the United States. That’s a ruling that should not stand.”

Scathing criticism of U.S. human rights record at UN review

The United States came under sustained criticism last week during a two-day review by the United Nations Human Rights Committee for its compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), a legally binding treaty ratified by the United States in 1992.

Much of the attention that the review has received in the media has focused on the U.S.’s refusal to recognize the ICCPR’s mandate over its actions beyond its own borders, using the “extra-territoriality” claim to justify its actions in Guantánamo and in conflict zones.

Walter Kälin, a Swiss international human rights lawyer who sits on the committee, criticized the U.S. position. “This world is an unsafe place,” Kälin said. “Will it not become even more dangerous if any state would be willing to claim that international law does not prevent them from committing human rights violations abroad?”

Besides its controversial counter-terrorism tactics, including indefinite detention and the use of drones to kill terrorist suspects far from any battlefield, the U.S. also came under criticism for a litany of human rights abuses that included NSA surveillance, police brutality, the death penalty, rampant gun violence and endemic racial inequality.

The U.S. government was also reprimanded for the treatment of youth in the criminal justice system, with committee members pointing out that the sentence of life without parole for child offenders may raise issues under article 7 of the ICCPR, which prohibits “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” While this matter is left to the states under the U.S. system of federalism, the national government should require that juveniles be separated from adult prisoners, the U.S. was told.

Corporal punishment of children in schools, detention centers and homes was also raised, with the U.S. delegation asked what policy has been adopted to eliminate corporal punishment and treat children as minors rather than adults in the criminal justice system. To this criticism, the U.S. responded that it is still “exceptional” in the U.S. for children to be tried in adult courts.

Concern was also expressed over mandatory deportation of immigrants convicted of nonviolent misdemeanors without regard to individual cases. Further, the U.S. has failed to meet international obligations for freedom of religious belief in relation to indigenous communities, the committee said.

The U.S. was asked for a timeline for closing the Guantanamo detention center, and concern was raised over the fairness of the military commissions set up to try terrorism suspects. The majority of Guantanamo detainees approved for transfer remain in administrative limbo, the U.S. was reminded.

When it comes to mass surveillance being conducted by the National Security Agency, the U.S. delegation was asked if the NSA surveillance is “necessary and proportionate,” and whether the oversight under the FISA court could be considered sufficient.

NSA surveillance raises concerns under articles 17 and 19 of the ICCPR, the U.S. was told. According to article 17,

1. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation.

2. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

Article 19 guarantees that,

1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

3. The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

Committee members also highlighted the Obama administration’s failure to prosecute any of the officials responsible for permitting waterboarding and other “enhanced interrogation” techniques under the previous administration.

The committee weighed in on the ongoing conflict between the CIA and the Senate Intelligence Committee, calling in particular for the U.S. to release a report on a Bush-era interrogation program at the heart of the dispute.

“It would appear that a Senator Dianne Feinstein claims that the computers of the Senate have been hacked into in the context of this investigation,” Victor Manuel Rodriguez-Rescia, a committee member from Costa Rica, told the U.S. delegation.

“In the light of this, we would like hear a commitment that this report will be disclosed, will be made public and therefore be de-classified so that we the committee can really analyze what follow-up you have given to these hearings.”

Committee chair Nigel Rodley, a British law professor and former UN investigator on torture, suggested lawyers in the Bush administration who drew up memorandums justifying the use of harsh interrogation techniques could also be liable to prosecution.

“When evidently seriously flawed legal opinions are issued which then are used as a cover for the committing of serious crimes, one wonders at what point the authors of such opinions may themselves have to be considered part of the criminal plan in the first place?” Rodley said.

“Of course we know that so far there has been impunity.”

This impunity stems in part from the U.S. position that the treaty imposes no human rights obligations on American military and intelligence forces when they operate abroad, rejecting an interpretation by the United Nations and the top State Department lawyer during President Obama’s first term.

“The United States continues to believe that its interpretation — that the covenant applies only to individuals both within its territory and within its jurisdiction — is the most consistent with the covenant’s language and negotiating history,” Mary McLeod, the State Department’s acting legal adviser, said during the session.

This narrow legal reasoning drew criticism from the UN panel, with committee member Yuji Iwasawa, Professor of International Law at the University of Tokyo, pointing out that “No state has made more reservations to the ICCPR than the United States.”

The review last week, held on March 13-14, is a voluntary exercise, repeated every five years, and the U.S. will face no penalties if it ignores the committee’s recommendations, which will appear in a final report in a few weeks’ time.

The Guardian noted however that “the U.S. is clearly sensitive to suggestions that it fails to live up to the human rights obligations enshrined in the convention – as signalled by the large size of its delegation to Geneva this week. And as an act of public shaming, Thursday’s encounter was frequently uncomfortable for the U.S.”

U.S. human rights record under international review this week in Geneva

As a country that feels comfortable proudly proclaiming its “exceptional” status to the world and relishing in its perceived global leadership on human rights, the United States might find it somewhat uncomfortable being scrutinized this week on its own human rights record, when it is reviewed March 13-14 by the UN’s Human Rights Committee (HRC) for its compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), a legally binding treaty ratified by the United States in 1992.

As a country that feels comfortable proudly proclaiming its “exceptional” status to the world and relishing in its perceived global leadership on human rights, the United States might find it somewhat uncomfortable being scrutinized this week on its own human rights record, when it is reviewed March 13-14 by the UN’s Human Rights Committee (HRC) for its compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), a legally binding treaty ratified by the United States in 1992.

The review, which takes place every several years, is a rare spotlight on domestic human rights issues within the United States, as well as its prosecution of the “war on terror” abroad. It is one of the few occasions where the U.S. government is compelled to defend its record on a range of human rights concerns, speaking the language of international law rather than the usual language of constitutional rights.

One of the primary issues the United States will be asked to clarify this week is the applicability of the ICCPR to its military engagements overseas, including indefinite detention and the extrajudicial killings carried out by unmanned aerial vehicles, or drones.

Ben Emmerson, UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, has just completed an investigation into 37 recent drone strikes, in which he noted a sharp rise in strikes and a “significant number” of civilian casualties since the end of 2013. Emmerson has demanded greater accountability and transparency on drone strikes, including public investigations into allegations of civilian casualties.

In its questionnaire to the U.S. government ahead of this year’s review, the top question of the HRC was for clarification of the government’s position on the applicability of the ICCPR in the war on terror.

Specifically, the HRC requested that the U.S. clarify “the State party’s understanding of the scope of applicability of the Covenant with respect to individuals under its jurisdiction but outside its territory; in times of peace, as well as in times of armed conflict.”

Following the last review of the United States, in July 2006, the U.S. government articulated “its firmly held legal view on the territorial scope of application of the Covenant,” namely that the ICCPR does not apply to U.S. actions with respect to individuals under its jurisdiction but outside its territory, nor in time of war.

The HRC objected to this “restrictive interpretation made by the State party of its obligations under the Covenant,” and urged the U.S. to “review its approach and interpret the Covenant in good faith, in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to its terms in their context, including subsequent practice, and in the light of its object and purpose.”

Specifically, in its response to the U.S. report, the HRC urged the United States to:

(a) acknowledge the applicability of the Covenant with respect to individuals under its jurisdiction but outside its territory, as well as its applicability in time of war;

(b) take positive steps, when necessary, to ensure the full implementation of all rights prescribed by the Covenant; and

(c) consider in good faith the interpretation of the Covenant provided by the Committee pursuant to its mandate.

It does not appear, however, that the U.S. will be changing its legal position regarding the treaty’s extraterritorial applicability. As the New York Times reported on March 6,

The United Nations panel in Geneva that monitors compliance with the rights treaty disagrees with the American interpretation, and human rights advocates have urged the United States to reverse its position when it sends a delegation to answer the panel’s questions next week. But the Obama administration is unlikely to do that, according to interviews, rejecting a strong push by two high-ranking State Department officials from President Obama’s first term.

Caitlin Hayden, a National Security Council spokeswoman, declined to discuss deliberations but defended the existing interpretation of the accord as applying only within American borders. Called the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, it bars such things as unfair trials, arbitrary killings and the imprisonment of people without judicial review.

However, in a 56-page internal memo, the State Department’s former top lawyer, Harold Koh, concluded in October 2010 that the “best reading” of the accord is that it does “impose certain obligations on a State Party’s extraterritorial conduct.”

Despite Koh’s opinions, the Obama administration has reportedly decided not to reverse the previous U.S. position due to fears that accepting that everything from extraterritorial drone strikes to NSA surveillance could fall within the purview of the ICCPR.

The ACLU’s Jamil Dakwar pointed out in a blog post on Sunday that “the review will cast light on a dark underbelly of American exceptionalism — our refusal to acknowledge that human rights treaties have effect overseas.” The only other country in the world that claims that human rights treaties don’t apply to extraterritorial action is Israel, Dakwar noted.

Perhaps anticipating a difficult review, the United States is sending a huge delegation of government lawyers and military officials to defend the U.S. position. The HRC apparently had to reserve a bigger hall to accommodate the sizable U.S. government delegation and more than 70 human rights advocates and observers who will be in attendance at the six-hour session.

In addition to issues related to the global war on terror, the HRC will review U.S. compliance with its ICCPR obligations on matters such as the rights of indigenous peoples, the death penalty, solitary confinement, voting rights, migrant and women’s rights, and NSA surveillance.

The ACLU submitted a shadow report to the committee highlighting examples of accountability gaps between U.S. human rights obligations and current law, policy, and practice. “U.S. laws and policies remain out of step with international human rights law in many areas,” notes the ACLU.

In addition, the ACLU provided an update to the issues covered in its September submission to the committee, which addresses serious rights violations that have emerged in recent months. The report covers:

- Anti-Immigrant Measures at the State and Federal Levels

- U.S.-Mexico Border killings and Militarization of the Border

- Solitary Confinement

- The Death Penalty

- Accountability for Torture and Abuse During the Bush Administration

- Targeted Killings

- NSA Surveillance Programs

The U.S. Human Rights Network has also submitted 30 shadow reports and currently has a delegation in Geneva, conducting activities over the course of the week to ensure that UN and U.S. officials understand the human rights realities of communities across the country.

USHRN’s shadow reports cover a wide range of issues including indigenous rights, equal protection of men and women, prisoners’ rights, freedom of association, political participation, and access to justice. The Center for Constitutional Rights has submitted shadow reports on issues including police departments’ stop-and-frisk policies, deportations of immigrants, and arbitrary detention at Guantanamo Bay.

As the ACLU’s Jamil Dakwar wrote on Sunday,

More than ever, the U.S. is facing an uphill battle to prove its bona fides on human rights issues. The United States is not only seen as a hypocrite, resisting demands to practice at home what it preaches abroad, it is now increasingly seen as a violator of human rights that is setting a dangerous precedent for other governments to justify and legitimize their own rights’ violations.

Despite this fact, the U.S. continues to ruffle feathers around the world with its increasingly hypocritical criticisms of other countries. On February 27, the State Department released its annual human rights report on the global human rights situation. As Secretary of State John Kerry said in releasing the report:

Even as we come together today to issue a report on other nations, we hold ourselves to a high standard, and we expect accountability here at home too. And we know that we’re not perfect. We don’t speak with any arrogance whatsoever, but with a concern for the human condition.

Our own journey has not been without great difficulty, and at times, contradiction. But even as we remain humble about the challenges of our own history, we are proud that no country has more opportunity to advance the cause of democracy and no country is as committed to the cause of human rights as we are.

Kerry’s comments not only likely infuriated the frequent targets of U.S. criticism, but also were offensive to every other country on earth that takes the cause of human rights seriously. By saying that “no country is as committed to the cause of human rights as” the U.S., what he’s really saying is that even countries such as Iceland or Denmark which have made human rights core pillars of their foreign policy don’t come close to the U.S. standard.

Not unexpectedly, China and Russia immediately denounced the U.S. human rights report, saying the United States is hardly a bastion of human rights standards and is on poor footing to judge other nations.

“The United States always wants to gossip and remark about other countries’ situations, but ignores its own issues. This is a classic double standard,” said Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Qin Gang.

The combination of the U.S. drone assassination programs, a National Security Agency under increasing global scrutiny for its dragnet surveillance practices, rampant gun violence, poor labor standards, and use of solitary confinement in jails shows that the U.S. is hardly without its own human rights abuses, noted China in its own report, “The Human Rights Record of the United States in 2013.”

Moscow concurred, with Russian Foreign Ministry’s commissioner for human rights, democracy and supremacy of law Konstantin Dolgov saying on March 4 that the U.S. human rights report “has the same flaws that were typical for previous similar reports.”

“The document is cramped with selective and stereotype assessments with the use of double standards, for instance, regarding tragic events in Ukraine,” Dolgov noted.

He pointed out that the U.S. has “acute problems with equal suffrage rights in the US and their equal access to justice.” Further, the U.S. leads the world with the number of incarcerated citizens, with with 2.2 million prisoners, Dolgov said.

As the U.S. is forced to answer for its own human rights record this week, it will be interesting to see how forthcoming it is on these problems, or if it will continue to tout its claimed status as the human rights champion of the world.

The entire U.S. ICCPR review, taking place March 13 and 14, will be broadcast live on UN TV. To follow on Twitter, use the hashtag #ICCPRforAll.

For Compliance Campaign’s archive of ICCPR related articles, see here.

What if there were international repercussions for U.S. aggression?

Setting aside for a moment the question of whether there was any justification for the Russian Federation to deploy troops to Ukraine’s autonomous region of Crimea in order to “defend our citizens and our compatriots” as Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov told UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon on Monday, the intense international condemnation of that action raises another question: why is there never any comparable response to U.S. acts of aggression? And, if there were threats of genuine international repercussions, would it modify U.S. behavior at all?

Since Russia sent troops into Crimea, the United States and United Kingdom announced boycotts of the Sochi Paralympic Games, European Union leaders called a special summit at which they are expected to suspend talks with Russia on economic cooperation and liberalized visa rules, the U.S. suspended trade negotiations and all military-to-military engagements with Russia, U.S. lawmakers discussed sanctions on Russia’s banks and freezing assets of Russian public institutions and private investors, the Group of Seven major industrialized nations canceled preparations for the G8 summit that had been scheduled to take place in Sochi in June, and there is even talk of expelling Russia from the G8 altogether.

The Obama administration continues to discuss further ways to isolate and punish Russia, with members of the White House’s National Security Council spending more than two hours in the Situation Room on Monday discussing the administration’s options for pursuing additional diplomatic and economic consequences for Moscow.

“I think the world is largely united in recognizing that the steps Russia has taken are a violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty, Ukraine’s territorial integrity; that they’re a violation of international law; they’re a violation of previous agreements that Russia has made with respect to how it treats and respects its neighbors,” Obama said.

In short, the international response to Russia’s intervention could hardly be stronger. But even if this uproar is fully warranted (and there are certainly some doubts whether that is the case), it begs the question of why there has been such little international outcry, relatively speaking, over the decade-plus old war on terror that has violated the sovereignty and territorial integrity of countless countries, including most prominently, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Libya. When it comes to the U.S.’s ongoing drone wars, there have been some grumblings from the international community over concepts such as transparency, distinction, proportionality and sovereignty, but nothing along the lines of the international response to Russia’s Ukraine incursion.

It should be remembered that while the world is transfixed on this so far bloodless incursion of Russian forces into Ukrainian territory, the United States military deployed military forces to more than 130 countries last year, in near total secrecy.

As a January 16 report by journalist Nick Turse explained,

In 2013, elite U.S. forces were deployed in 134 countries around the globe, according to Major Matthew Robert Bockholt of SOCOM Public Affairs. This 123% increase during the Obama years demonstrates how, in addition to conventional wars and a CIA drone campaign, public diplomacy and extensive electronic spying, the U.S. has engaged in still another significant and growing form of overseas power projection. Conducted largely in the shadows by America’s most elite troops, the vast majority of these missions take place far from prying eyes, media scrutiny, or any type of outside oversight, increasing the chances of unforeseen blowback and catastrophic consequences.

So, the United States is operating in 134 countries around the world (more than half of the total number of UN Member States), and its actions elicit barely a whimper of complaint, but Russia sends forces to one country (arguably on a much firmer pretext and rationale), and the international community reacts as if World War III has just been declared.

The double standards are mind-boggling, and beg the question “why?”

Of course, we all know that the United States is the world’s economic and military powerhouse, but does that fully explain it? Perhaps the U.S. has just been throwing its weight around for so long – invading countries on a whim, disregarding international norms, violating territorial integrity and national sovereignty – that it all seems normal at this point. Or perhaps the U.S. and its allies actually fundamentally agree on the virtue of U.S. military action, and share the same view on Russia: namely that Russia is a negative force in world affairs that must be neutralized at any cost.

If this is the case, it seems that the international community as a whole is just as hypocritical as the United States is, and lacks any sort of guiding principle on what constitutes “normative behavior.” On the other hand, if nations are just afraid of standing up to the bully on the playground, one wonders what might happen if they ever do grow a spine. Perhaps U.S. lawlessness and military adventurism might finally be reined in.

U.S. pronouncements on international law carry little weight with Russia

As Washington responds with shock and outrage over the deployment of Russian troops to the Crimean Peninsula of Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin has stressed that if violence spreads in the eastern regions of Ukraine and Crimea, Russia reserves the right to protect its interests and the Russian-speaking population.

In a telephone conversation with German Chancellor Angela Merkel on Sunday, Putin reportedly said that Russian citizens and Russian-speakers in Ukraine faced an “unflagging” threat from ultranationalists, and that the measures Moscow has taken – mainly sending troops to serve as a buffer between Ukrainian military forces and the local population – were appropriate given the “extraordinary situation.”

This situation includes outbreaks of violence between Ukrainian nationalists and Russian loyalists, as well as official acts of the newly formed Ukrainian government that have been widely seen as discriminatory against the Russian-speaking population. Last week, pro- and anti-Russian demonstrators clashed in front of the parliament building in Simferopol, the capital of Ukraine’s autonomous Crimea Region, leading to several hospitalizations and at least two deaths.

“Demonstrators slammed each other with flags and threw stones as leaders on both sides urged their followers to avoid provocations,” reported RT.

Further, Russia’s Federal Migration Service said it has seen a sharp spike in applications from Ukrainian citizens seeking refuge from outbreaks of violence following a U.S.-backed coup that toppled the government of Viktor Yanukovych on Feb. 22. As RIA Novosti reports,

The head of the migration service’s citizenship department, Valentina Kazakova, said 143,000 people had applied for asylum in the last two weeks of February alone.

“People are afraid for the fate of those close to them and are asking not just for protection, but also to help them receive fast-tracked Russian citizenship,” Kazakova said. “A large number of applications are from members of Ukrainian law enforcement bodies and government officials fearing reprisals from radically disposed groups.”

Many people living in Crimea, a 10,000-square mile peninsula on the Black Sea with historical and linguistic ties to Russia, agree with Moscow’s assertion that Ukraine’s revolutionaries are violent, western-backed far-right ultranationalists who intend to roll back the rights of Russian-speakers and restrict Crimea’s links with Russia itself.

Unfortunately, the actions of the Ukrainian government following the ouster of President Yanukovych have largely confirmed these fears. Last week, Ukraine’s parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, began immediately moving to prohibit the official use of the Russian language in Ukraine and block broadcasts of Russian television and radio programs in the country.

The Verkhovna Rada’s repeal of the law on the “Principles of the State Language Policy,” which provided for the use of the Russian language in Russian-speaking parts of Ukraine, could lead to further division and unrest, warned the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities Astrid Thors.

“The authorities have to consult widely to ensure that future language legislation accommodates the needs and positions of everyone in Ukrainian society, whether they are speakers of Ukrainian, Russian or other languages,” said Thors.

In response to the blocking of Russian broadcasts, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, Dunja Mijatovic, noted in a letter to Oleksandr Turchinov, Acting President of Ukraine and Chair of the Verkhovna Rada, that “Banning broadcasts is one of the most extreme forms of interference in media freedom and should only be applied in exceptional circumstances.”

It is in this context of official suppression of Russian rights, as well as the sporadic violence leading to a dramatic spike in asylum seekers, that Putin sought authorization from the Russian Parliament to deploy military forces to Crimea. Putin said he proposed military action because of “the threat to the lives of citizens of the Russian Federation,” and the Parliament passed his proposal unanimously.

Although no shots have been fired by the Russian troops and a Ukrainian colonel was quoted as saying that the Ukrainian and Russian sides had “agreed not to point our weapons at one another,” the presence of Russian forces in Ukraine is being denounced in the strongest terms by U.S. officials, including President Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry.

Appearing on ABC News’ This Week on Sunday, Kerry said,

What has already happened is a brazen act of aggression, in violation of international law and violation of the UN Charter and violation of the Helsinki Final Act. In violation of the 1997 Ukraine-Russia basing agreement. Russia is engaged in a military act of aggression against another country, and it has huge risks, George. It’s a 19th century act in the 21st century. It really puts at question Russia’s capacity to be within the G-8.

If the United States had a truly free press, the outrage expressed by the U.S. Secretary of State over the Russian deployment of troops and its alleged violation of international law would lead any honest journalist to follow up with a question like, “Excuse me, Mr. Secretary, but how can you possibly feign such outrage with a straight face when we all know that the U.S. has repeatedly invaded foreign countries and habitually violated the UN Charter with impunity for years? What gives the United States the moral authority or credibility to be the arbiter of international law and the legitimate use of force?”

Instead, George Stephanopoulos followed up with, “I understand it’s a violation, sir. So what’s the penalty for what Russia has already done?”

To which Kerry responded:

Well, we are busy right now coordinating with our counterparts in many parts of the world. Yesterday, the president of the United States had an hour and a half conversation with President Putin. He pointed out importantly that we don’t want this to be a larger confrontation. We are not looking for a U.S.-Russia, East-West redux here. What we want is for Russia to work with us, with Ukraine. If they have legitimate concerns, George, about Russian speaking people in Ukraine, there are plenty of ways to deal with that without invading the country. They have the ability to work with the government, they could work with us, they could work with the UN. They could call for observers to be put in the country. There are all kinds of alternatives. But Russia has chosen this aggressive act, which really puts in question Russia’s role in the world and Russia’s willingness to be a modern nation and part of the G8.

Incidentally, the 90-minute phone call between Putin and Obama that Kerry referred to was initiated by the Russian president, who called Obama to explain why Russia was sending troops to the Crimean Peninsula. The Russian government released a statement on the phone call, which reads:

In response to the concern shown by Barack Obama regarding possible plans of the use of Russian armed forces on the territory of Ukraine, Vladimir Putin drew attention to the provocative criminal acts by ultra-nationalist elements, which are in fact encouraged by the current authorities in Kiev.

The Russian President stressed the existence of real threats to the lives and health of Russian citizens and compatriots on Ukrainian territory. Vladimir Putin stressed that in the case of further spread of violence in the eastern regions of Ukraine and Crimea, Russia reserves the right to protect its interests and the Russian-speaking population.

The White House’s readout of the phone call was quite different. According to an account posted on the White House website,

President Obama expressed his deep concern over Russia’s clear violation of Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity, which is a breach of international law, including Russia’s obligations under the UN Charter, and of its 1997 military basing agreement with Ukraine, and which is inconsistent with the 1994 Budapest Memorandum and the Helsinki Final Act. The United States condemns Russia’s military intervention into Ukrainian territory. …

President Obama made clear that Russia’s continued violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity would negatively impact Russia’s standing in the international community. In the coming hours and days, the United States will urgently consult with allies and partners in the UN Security Council, the North Atlantic Council, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and with the signatories of the Budapest Memorandum. The United States will suspend upcoming participation in preparatory meetings for the G-8. Going forward, Russia’s continued violation of international law will lead to greater political and economic isolation.

It is clear from this statement that the United States is committing itself to a confrontational course that intends to rally the world in isolating the Russian government, including perhaps by expelling Russia from the G-8. But as the AP reported on Saturday,

Despite blunt warnings about costs and consequences, President Barack Obama and European leaders have limited options for retaliating against Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine, the former Soviet republic now at the center of an emerging conflict between East and West.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has so far dismissed the few specific threats from the United States, which include scrapping plans for Obama to attend an international summit in Russia this summer and cutting off trade talks sought by Moscow.

“There have been strong words from the U.S. and other counties and NATO,” said Keir Giles, a Russian military analyst at the Chatham House think tank in London. “But these are empty threats. There is really not a great deal that can be done to influence the situation.”

Perhaps what the U.S. hopes is that simply reminding Russia of its “obligations under international law” will somehow lead to changes in Russian policy; that Moscow will just bend to the will of Washington on this issue. The problem is, U.S. pronouncements about international law are largely empty rhetoric, and no one is more aware of this than the Russians.

It was just last summer that the Russian government was admonishing the Obama administration for its drive to war with Syria, largely basing its opposition to a possible U.S. bombing campaign on the grounds of international law.

“The potential strike by the United States against Syria,” Putin wrote in an op-ed published by The New York Times, “despite strong opposition from many countries and major political and religious leaders, including the pope, will result in more innocent victims and escalation, potentially spreading the conflict far beyond Syria’s borders. … It could throw the entire system of international law and order out of balance.”

Putin also chided the U.S.’s over-reliance on military force to settle its disputes, including in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and the narrowly averted intervention in Syria:

It is alarming that military intervention in internal conflicts in foreign countries has become commonplace for the United States. Is it in America’s long-term interest? I doubt it. Millions around the world increasingly see America not as a model of democracy but as relying solely on brute force, cobbling coalitions together under the slogan “you’re either with us or against us.”

But force has proved ineffective and pointless. Afghanistan is reeling, and no one can say what will happen after international forces withdraw. Libya is divided into tribes and clans. In Iraq the civil war continues, with dozens killed each day. In the United States, many draw an analogy between Iraq and Syria, and ask why their government would want to repeat recent mistakes.

With all those military interventions in its recent past – all carried out in violation of the UN Charter – the U.S. is certainly in no position now to lecture Russia on international law, and Moscow knows this.

Then of course, there is also the matter of the U.S.’s drone wars – the ongoing remote-controlled bombing campaigns of countries including Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan. Just last week, the UN Special Rapporteur on terrorism and human rights, Ben Emmerson, published the second report of his year-long investigation into drone strikes, highlighting dozens of strikes where civilians have been killed.

The report identifies 30 attacks between 2006 and 2013 that show sufficient indications of civilian deaths to demand a “public explanation of the circumstances and the justification for the use of deadly force” under international law.

But somehow the U.S. manages to get a pass when it comes to these unpleasant realities, and is able to maintain a veneer of credibility when it rebukes others for violating international law. At least as far as Russia’s concerned though, these rebukes are not likely to work.